German military burials are notable because of their tendency to inter their soldiers in pairs. This is a feature of German cemeteries in mainland Europe, and also in Ireland’s German cemetery in Glencree Co. Wicklow. In German it is referred to as Comrades in Death (Kameraden in den Tod).

The concept of men who fought side by side being buried together is a touching one. After all, they paid the ultimate sacrifice together. They were, on the face of it, fighting for a common cause even though the personal reasons for doing so varied from soldier to soldier. Irishmen volunteered and fought alongside English, Scots and Welsh in the First World War for multitudes of reasons. These ranged from the purely financial, the hope that Home Rule would be granted, all the way to pure family tradition where the father was in the military and was followed by his sons.

This all changed on the 24th of April 1916 when the (at the time deeply unpopular) Rebellion in Dublin started. From that day forward Irishmen in the British army found themselves in the impossible position of having to aim down their rifle barrels at fellow Irishmen who happened to be Republican volunteers.

180 civilians and “insurgents” were killed and 614 wounded during the disturbances.

Ireland has always had a discomfort surrounding the commemoration of those who fought on the British side. This has been addressed in recent years with State commemorations of these men now commonplace.

On a more personal level, there is a little-known corner of Dublin where those who are interested will find it is possible to commemorate both IRA Volunteers and British Army casualties who lie, quite literally, side-by-side; Comrades in Death. Here, unusually, Easter lilies and poppies are equally welcome.

The burial place in question is situated in the grounds of what is now the Health Service Executive (HSE) building opposite Heuston Station.

The building was formerly Dr. Steeven’s Hospital and was built to cater for the poor and destitute. It was founded in 1717.

Walking across the road outside Heuston station you will come across a vehicular security barrier at the right of the building (access for pedestrians is not a problem). Walk straight ahead and through an open doorway in a wall you will enter a courtyard containing some Portakabins.

In the corner facing you, you will see two gravestones.

The area from the security barrier to this point is marked “Steeven’s Hospital Burial Ground” in the 1847 Ordnance Survey Town Plans of Dublin. This would indicate that this whole area was originally a pauper’s graveyard, especially when one considers the function of the original hospital. It is also safe to assume that there are hundreds of unmarked burials all around this area.

The British Army men (mostly Irish) in question, marked with a British standard Commonwealth War Grave stone, are:

4628 Private George William Barnett, Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment) 2/8th Battalion

Resided in Loughborough, Leicester England. Enlisted in Newark, Nottinghamshire, Killed in action on 27 Apr 1916

Here is Pte. Barnett's service record entry showing him as a KIA:

7022 Private Oscar Bentley, Household Cavalry and Cavalry of the Line, 5th Lancers (Royal Irish)

Born Welshpool, Montgomeryshire, resided in Blackpool, enlisted in Preston

Killed in action on 24 Apr 1916

Here is Pte. Bentley's medal entitlement card showing place of death:

9852 Private Michael Carr, Royal Irish Regiment 3rd Battalion

Resided: Mulhuddart, Co. Dublin. Killed in action 24 Apr 1916. Enlisted Dublin

9947 Private James Duffy Royal Irish Regiment, 3rd Battallion

Born Carisvilla, Co. Kildare, Died of wounds on 24 Apr 1916 Enlisted in Limerick

11162 Private Thomas Treacy Royal Irish Regiment 3rd Battalion

Born and resided in Mordike, Co. Tipperary, Died of wounds on 24 Apr 1916, Enlisted in Clonmel, Co. Tipperary

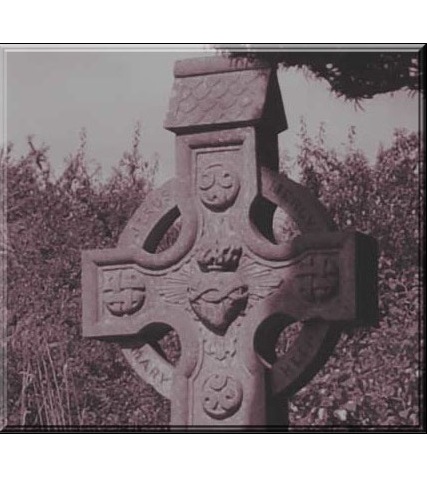

The IRA Volunteers’ resting place is marked with a National Graves Association scroll-type “Oglaigh na hEireann” memorial. These men were:

Volunteer Sean Owens 4th Battalion Dublin Brigade, Irish Volunteers.

Resided in The Coombe. He appears as John Owens aged 8 years in the census of 1901, the son of a Tea Merchant’s Labourer. He was killed in the taking of the South Dublin Union aged 24

Volunteer Peter Wilson, Fingal Brigade, Irish Volunteers, was the son of an Agricultural Labourer and was killed by British forces after the surrender of the Mendicity Institution despite emerging holding a white flag.

Whatever the reason for these men being interred in such an unusual location, it makes the old arguments about commemoration appear nonsensical. The existence of these men’s burials in such close proximity could have given the Irish Government an ideal opportunity and location to give ALL of the casualties of 1916 (and by extension their Irish comrades buried in mainland Europe and further afield) the remembrance they deserved instead of consigning the memory of Irishmen in British uniform to oblivion for half a century.

Ar dheis Dé go raibh a n-anam